Tall-Case Clock Expands Scholarship in Lower Southern Piedmont

April 12th, 2015

|

Note the fine reeded panels on this circa 1815 tall-case clock attributed to James Mattison, Anderson County, South Carolina. See article for the full story. Dealer Keith McCurry bought the Mattison clock for $22,800 (est. $4000/6000). It was the top lot of the sale.

Provenance was conspicuously displayed on the face of this 14¼" x 12½" stoneware jar—name (Sam Whelchel), date (1895), location (Gaffney, South Carolina), and volume (five gallons). Dr. Philip Toussaint bought it for $11,400 (est. $4000/6000). This was the top-dollar pot of the sale.

Jeremy Wooten led off the miniature furniture lots with the oldest and, as it turned out, the priciest. The 27¾" x 25¼" x 12½" tiger maple desk with white pine secondary was attributed to a New England maker circa 1770. An Internet bidder beat back six phone bidders to take it for $6600 (est. $3000/5000).

A 29 3/8" x 17 5/8" x 13¼" southern walnut and cherry spice or valuables cabinet with compartmentalized interior went to Philip Toussaint for $10,200 (est. $3000/5000).

The Wootens found no other examples of an original menu for a 1908 dinner honoring Mark Twain. It sold to an Internet bidder for $540 (est. $200/300). The dinner at the Lotos Club in New York City must have been quite a literary affair. The menu included Innocent Oysters Abroad, Roughing It Soup, and Life on the Mississippi Ice Cream.

A collector from Atlanta, Georgia, consigned six Connoisseur of Malvern porcelain animal figures. These limited-edition porcelains crafted by various artists were produced in England. Derided as “instant antiques,” they have been showing up at auctions in the United States. The Snow Leopard topped all and provided moments of conflict between two floor bidders sitting next to each other. The two were deferential before the Snow Leopard came up, with one buying three Malverns and the other taking two. With Snow Leopard, cooperation went out the window. The 20½" x 36½" x 12" figure by Christoper Ashenden sold for $3840 (est. $1000/1500) to the floor bidder who had purchased three other Malvern figures. The score at the end of six rounds was 4 to 2.

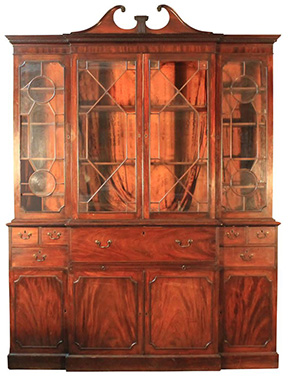

Over-the-top geometric mullions decorated the four glazed doors on this late 18th-century George III mahogany breakfront bookcase. The lower case has a fall-front butler’s desk above four cupboard doors. It opened at $5000 and sold to a phone bidder for $11,400 (est. $4000/6000). |

Wooten & Wooten, Camden, South Carolina

Photos courtesy Wooten & Wooten

Gary Thompson’s utilitarian pottery collection led off the Wooten & Wooten sale held April 11 and 12, but it was his circa 1815 tall-case clock that stole the show. Antiques dealer Keith McCurry of Belton, South Carolina, who purchased the clock for $22,800 (includes buyer’s premium), said that the signed clock solved a mystery that he and Dale Couch, a curator at the Georgia Museum of Art, have investigated for years. In a phone conversation following the sale, McCurry said, “The clock ties together an entire group of work from the lower southern Piedmont backcountry,” an area that has received scant attention in decorative arts research.

Until now the so-called Reeded Raised Panel Group was not associated with a particular furniture craftsman. Now it seems that James Mattison (1762-1849), a Virginia furniture maker who settled in what is present-day Anderson County, South Carolina, may have been a member of a woodworking family that created much of the group.

Through an inscription to William Halbert Mattison, the Wootens attributed the Thompson clock to William’s grandfather James Mattison. The clock has finely reeded panels at the top of the column capital just below the hood and between the dial door and the frieze. “Although the clock does not have raised reeded panels, it is part of a large group of objects, some of which do have that rare feature,” said Dale Couch. He spoke with M.A.D. ten days after the Wooten sale. “We will analyze the clock to see how its construction connects to the group. We are still identifying [characteristics] of the group.”

James Mattison and a huge clan of relatives resided in the lower southern Piedmont, an area that extends from Spartanburg, South Carolina, to Atlanta, Georgia. Settled years after the end of the Revolutionary War, the area defined backcountry. Tall-case clocks like Mattison’s were signs of affluence anywhere in the South, but in remote areas like Anderson County, they were especially rare. Its case is mahogany-stained poplar, an indication of its humble origin. By circa 1815, the date determined by Wooten and his staff for the Mattison clock, mantel clocks had begun to replace tall-case clocks in the more urban areas of the South, said Couch.

“I believe the [Reeded Raised Panel] group is of northern European origin, probably Swedish,” said Couch. Mattison may sound like a British name, but Couch believes that it was originally Scandinavian. The name can be found in Britain because of Viking settlement, said Couch, and there is evidence that late 18th-century members of the Mattison family were direct emigrants from Continental Europe to Virginia.

More research is needed, of course, but the Mattison clock gave the Reeded Raised Panel Group a name it had previously lacked.

In addition to the Mattison clock, 25 other southern furniture lots populated the April sale. Among the bestsellers was an early 19th-century walnut and cherry spice or valuables cabinet probably from Winchester, Virginia. The small chest sold for $10,200. A circa 1820 Federal inlaid walnut chest from the school of James McCann of the New Market, Virginia, region, brought $5760. Both lots were purchased by Philip Toussaint, a neurosurgeon in Columbia, South Carolina.

The pottery portion of Gary Thompson’s consignment brought together collectors who regard the Edgefield District of upstate South Carolina as the center of the pre-Civil War pottery universe. The last time these gentlemen gathered to greet and then attempt to assassinate each other when bidding for southern pottery was here in Camden for the Ferrell sale (see M.A.D., April 2014).

Among the Ferrell alumni was Phil Wingard, a collector and dealer in Edgefield pottery for the past 30-plus years. During the Thompson sale, many checked to see if Wingard was bidding. His participation seemed to guarantee that a pot was worth blowing past the high estimate. And these estimates meant something. They came from auctioneer Jeremy Wooten, who in an earlier life was a southern pottery picker for many of the major southern auction houses.

While the Ferrells had undamaged pots signed by Edgefield rock stars such as Collin Rhodes, Thomas Chandler, Abner Landrum, and enslaved poet-potter Dave, Thompson’s 71 pots featured some of South Carolina’s lesser lights.

The top Thompson lot was a signed and dated (1895) stoneware storage jar by Sam Whelchel. Missing one handle, the rare Whelchel jar sold to Philip Toussaint for $11,400. Thompson’s second-highest pot was a circa 1890 stoneware jar signed by Rich Williams, one of South Carolina’s most important post-Civil War African American potters. The battle for the Williams jar came down to a phone bidder and Jim Williams bidding from the floor. The phone bidder won it for $9600.

Two other Whelchel jars from the Thompson collection sold above the high estimates. Both were circa 1880 stencil-decorated pieces from the Whelchel family of Spartanburg County. A Whelchel pitcher sold for $5520, and a 10¼" high storage jar brought $4800. The Whelchel family, including Sam and his son William, operated a small pottery from 1875 until the 1930s. Like many 19th-century Carolina potters, the Whelchels were related by marriage to other area potters.

Two non-Thompson pots came with curious back stories. A circa 1850 slave-made storage jar attributed to master potter Dave arrived at the auction house painted black. Jeremy Wooten chemically stripped the paint from the jar. “It won’t hurt the glaze,” he said. He sold it to collector Jim Williams for $5520. A few weeks before the sale, a picker brought in a circa 1845 decorated stoneware jug from the Rhodes Factory, Edgefield, South Carolina. The picker found the jug in a barn on the South Carolina coast and called Wooten. Amazing discoveries still happen. The “farm fresh” jug sold to a phone bidder for $4800.

A collection of 18th- and 19th-century miniature furniture attracted a flood of attention from phone and Internet bidders and hardly a trickle from the house. Thirteen carefully crafted chests, desks, tables, and blanket boxes were generally ignored during preview. The top-dollar miniature was a 27¾" high circa 1770 Chippendale tiger-maple desk made in New England. Behind the slant front was a fitted interior. The three graduated drawers and the case were dovetailed. The secondary wood was white pine. Six phones and the Internet jumped in, with a LiveAuctioneers bidder taking it for $6600.

Wooten & Wooten market their auctions as the place to buy and sell well-researched and important pieces of southern decorative arts like the Mattison clock. As more auction houses below the Mason-Dixon line embrace mid-century modern, there are fewer venues for southern cellarets, hunt boards, sugar chests, secretary bookcases, clocks, pottery, and everything else that people love about the South.

Recent Wooten & Wooten sales attended by M.A.D. have been standing room only for a good portion of the day. The long, narrow auction gallery would benefit from extra speakers by the front door. The current public address system doesn’t quite extend to the outer reaches of the gallery where conversations occasionally drown out the auctioneer.

Recent Wooten & Wooten sales attended by M.A.D. have been standing room only for a good portion of the day. The long, narrow auction gallery would benefit from extra speakers by the front door. The current public address system doesn’t quite extend to the outer reaches of the gallery where conversations occasionally drown out the auctioneer.

For more information on Wooten & Wooten, visit the website (www.wootenandwooten.com) or call (866) 570-0144.

|

Mississippi Abstract Expressionist Andrew Bucci died at age 92 in December 2014. The enthusiastic bidding from the phones and Internet for his signed but untitled 34¾" x 19" oil on canvas may have surprised the Wootens. Their estimate was $400/600. When it sold for $5760, Jeremy Wooten remarked, “That may be a near world record for him.” |

|

A phone bidder jumped the bid from $1100 to $2600 for this Newcomb College pottery vase. It is signed “JM Pottery Meyer, X” for Joseph Meyer, head potter at Newcomb from 1896 to 1927. Bidding was all on the phones, and it sold for $5040 (est. $1000/2000). |

|

Ken Lee opened the bidding at $1100 for this 10½" x 8½" Whelchel family decorated pitcher. Despite nicks around the rim, the pitcher sold for $5520 (est. $1500/2500). |

Originally published in the July 2015 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2015 Maine Antique Digest