The 50th Anniversary Delaware Antiques Show

November 7th, 2013

|

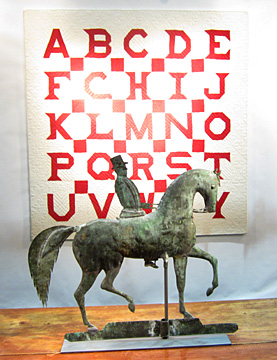

The red and white ABC quilt, pieced cotton, with a Betty Sterling provenance, was $8500 from Olde Hope Antiques, New Hope, Pennsylvania. The horse and rider copper weathervane, attributed to Jewell, was $28,000.

James Kilvington of Dover, Delaware, had an impressive offering, proving it is still possible to put together a collection of first-rate American furniture. The early Queen Anne Philadelphia high chest, 1735-40, was $65,000; the running horse weathervane on top, circa 1880, was $5200. The very tall clock, 8'9" high, is by Duncan Beard, Delaware’s most renowned clockmaker; it was $59,500. The clock to the right is by Thomas Crow, another Delaware maker, and was $39,600.

Taylor Williams of Chicago asked $14,000 for the English cast-iron bench marked “Colebrookdale.” The tray on stand was $6500; it is marked “Clay, King Street,” the name of a well-known London japanner.

This quirky Vermont veneered figured maple sideboard was $14,500 from Peter Eaton. It is $135,000 less than it was at the Winter Antiques Show in New York City when G.K.S. Bush offered it a decade ago, said Eaton. It was made in western Vermont; the secondary woods are cherry and poplar.

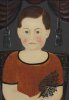

This rare walnut William and Mary chest of drawers attributed to John Head, 1730-40, was $18,500 from Skip Chalfant of H.L. Chalfant, West Chester, Pennsylvania. It sold in the last hour of the show. The portrait above it of Elizabeth Van Dyke Vosburg is one of the earliest Hudson River school portraits known; she married Martin Vosburg in 1725. In its original frame, it was $195,000 and was sold with a Van Dyke family bible that was printed in Amsterdam in 1792.

Arthur Liverant of Nathan Liverant and Son, Colchester, Connecticut, asked $14,500 for this very large Navajo Yei woven rug, 11'11" x 5'8", woven 1945-55. The bamboo Windsor bench, 1795-1810, was $13,500; the Windsor high chair, New England, 1770-95, was $18,500.

Samuel Herrup had this early Philadelphia chair, 1735-40, similar to one at the Wright’s Ferry Mansion on the Susquehanna River, #14 in the Wright’s Ferry book, on hold for the historic house. By the time the show was over Herrup had sold five chairs.

Elle Shushan (right) talks about the regional variations of portrait miniature frames with Anne Wagner of Winterthur and Janine Skerry of Colonial Williamsburg. A Virginia frame is reddish gold and has a wide border and a pronounced bezel and lips on the hoop from which it can be hung. A Boston frame of thin rolled cast foliate design gets wider further south. New York frames have no bezels on the back, and rural frames from Pennsylvania are gilded pressed tin. Regional styles of frames give a place to start when looking for the names of painters or sitters. |

Wilmington, Delaware

“I was here all day yesterday and all day today, and I haven’t made a dent, there are so many layers,” said Chester County collector Tom Helm at 4 p.m. on Sunday afternoon at the Delaware Antiques Show, held November 7-10, 2013, in Wilmington, Delaware. He had just an hour left before the dealers began packing up.

He was right. There was plenty of 18th- and 19th-century furniture, some of it walnut and mahogany, some Federal with veneers, some painted, and a dozen impressive tall-case clocks.

A Chester County walnut desk-and-bookcase, with the date 1744 and initials of the owner inlaid on the prospect door, was surely the rarest documented piece of Pennsylvania furniture offered. It is attributed to joiner Joel Baily Sr. (1697-1775) of West Marlborough Township, and the inlaid initials “I.M.” are most likely for John Marshall, the son of the founder of Marshallton. The desk was passed down in the family until 1953 when it was purchased by Titus Geesey, H.F. du Pont’s secretary and collecting colleague. It is illustrated in Margaret Schiffer’s book Furniture and Its Makers of Chester County and is related to a signed desk by Joel Baily Sr., also illustrated in Schiffer’s book. It was $72,500 from dealer Philip Bradley of Downingtown, Pennsylvania.

James Price said he had owned his schrank, with Moses inlaid on one door and Jesus Christ on the other, for 40 years but just got around to having it conserved by Alan Miller. His asking price was $270,000. He said it is related to a schrank at the Hershey Story (formerly the Hershey Museum of Early American Life), but he knows of no others. He kept it wrapped until just before the show opened at 5 p.m.

There were some first-rate Windsor chairs, bow-backs, comb-backs, settees, and high chairs for sale with James and Nancy Glazer, Arthur Liverant, and Joe Kindig. Federal furniture sold first. Jesse Goldberg of Artemis Gallery sold five pieces by Saturday that were reasonably priced.

Four dealers sold Chinese export porcelain, and they sold well. There was English creamware, pearlware, transferware, ironstone, delft, redware, and stoneware on a number of stands. American Tucker porcelain was on two stands.

There was needlework by skilled professionals and by schoolgirls. Dealer Grace Snyder offered an early embroidered pillow, possibly American, and Jenifer Kindig had seven panels of English blue needlework. There were plenty of samplers and needlework pictures from which to choose.

Christopher Rebollo had portraits by Charles Willson Peale and his son Raphaelle Peale. Portraits by naïve artists including Ammi Phillips (with dealer Joan Brownstein) and a little-known Framingham limner named Joseph Stone (at Stephen-Douglas) were compelling. Skip Chalfant had the earliest portrait. It was of Elizabeth Van Dyke Vosburg, painted in the Hudson River valley, circa 1725. There were seven profile portraits by a talented Dutch-born pastelist named Gerrit Schipper; three were with Elle Shushan and four with Samuel Herrup, all painted between 1802 and 1810. Joan Brownstein sold two miniatures by Mrs. Moses B. Russell (1808-1854) of Boston.

Not everything was made in America, but Americana dominated. Peter Eaton offered a Swedish chair from the 17th century, and Elliott and Grace Snyder had a carved Tyrolean bed smoother made a tad earlier. Mo Wajselfish of Leatherwood Antiques sold a lot of Vienna bronzes and German Black Forest carvings and small English Regency furniture. Barbara Israel sold English garden lions and two garden elephants.

Three weathervanes sold; one in the form of a Indian shooting an arrow was sold by the Garthhoeff-ners, and Edwin Hild and Patrick Bell at Olde Hope Antiques sold a gilded fish as did Diana Bittel.

Looking glasses sold. Jenifer Kindig sold five of them. Philip Bradley sold one with a John Elliot label, and several others changed hands. Sam Herrup sold five chairs. Ralph and Karen DiSaia sold four Oriental rugs. Steven Powers proved that the best sells. He sold a graduated set of three carved wooden bowls for which he was asking $85,000; there are none better. Jewelry dealers said sales were brisk.

This show comes at a good time of year, just two weeks before Thanksgiving when people are beginning to think about holiday gifts.

Expensive furniture is not a stocking stuffer, and not a lot of it sold right off, though much was being considered, and dickering continues long after the show closes. Several dealers reported most of their sales were made in the last hour. Jamie Price said in the weeks after the show closed he made 20 sales. “All those people who said ‘Let me try a piece and see how I like it’ decided to buy it.”

Chris Rebollo said he sold his Charles Willson Peale portrait of Amy Hunter Ewing Patterson of Greenwich, New Jersey, the wife of a doctor, after the show closed.

The Delaware show may not be the place where the most antiques change hands, but it is where much

knowledge is exchanged dealer to dealer, dealer to curator, dealer to student, and dealer to collector. It is not surprising that Judith Livingston Loto of Russack-Loto Books sells more books on decorative arts at this show than at any other. She said books on furniture and ceramics were big sellers this year, especially limited editions of regional studies and books on delft, Chinese export porcelain, and stoneware.

This was the 50th annual Delaware show, and it was celebrated with some special lectures. One on Friday at 10 a.m. by Lady Henrietta Spencer-Churchill was on the history of Blenheim Palace, her family’s Baroque country house and surrounding lands that has similar financing problems as Winterthur. On Sunday Barbara Paul Robinson, who wrote a biography of the legendary English gardener Rosemary Verey, whose clients include Prince Charles, Elton John, and countless Americans, told her audience that Rosemary Verey’s house and garden in the Cotswolds is now a country hotel. Barnsley House can be visited and the gardens toured. On Saturday Frank Hohmann III and Donald L. Fennimore spoke about the Stretch family of clockmakers, the subject of their new book. Like the other two lectures, it was followed by a book signing.

There was a low-budget loan exhibition at the entryway of a few objects that had been bought at the Delaware show over the years from local collections. Winterthur lent a quilt made from English chintz in a Gothic pattern.

The presentation of the first Wendell D. Garrett Award to Gerald Ward took place on Saturday at 6 p.m. Like Garrett, Ward has influenced a generation of readers through his writings and editing. He also served in curatorial positions at Winterthur and Strawbery Banke, and for the last 20 years as senior curator of American decorative arts at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. In November 2012, he was elected state representative for New Hampshire’s District 28 in Rockingham County, and he serves as a legislator while continuing as consulting curator at the MFA.

The preview party could have been more festive; the food was not celebratory, it was dreadful. The governor of Delaware was there; Tom Savage, Winterthur’s vice president, in charge of museum affairs, had him in tow. The governor could have given a champagne toast to congratulate those behind the show that has survived for 50 years and has moved its venue five times as it grew from a hospital benefit to benefit Winterthur’s educational programs in 1991. Diana Bittel, who has managed this show for the last four years, said it is a reasonable show to do, and Winterthur treats the dealers very well. This year with a new Westin hotel being built next door, more people will likely come. She said she has long waiting list of dealers who want to exhibit. In 2013 only four dealers were new to the show, three with country furniture and folk art—Jewett-Berdan from Maine, Stephen-Douglas from Vermont, and the Garthoeffners of Pennsylvania—and William Vareika Fine Arts from Newport. Stella Rubin returned after an absence of six years with quilts and jewelry.

Visiting the show is hard work but well worth it. The most scholarly dealers are there to educate, and those who come to the show belong to the generations that love learning about the furniture and furnishings they live with and are intent on developing their eye for quality. That is why multiple visits to this show are so rewarding. It seems to get better with every visit.

For more information, see (www.winterthur.org).

Originally published in the February 2014 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2014 Maine Antique Digest