The Metro Show 2014

January 22nd, 2014

|

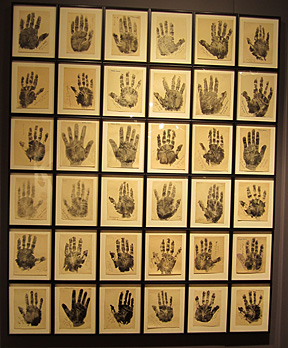

Ricco/Maresca, New York City, asked $35,000 for renowned palmist Marianne Raschig’s collectionof original vintage palm prints that she collected between 1925 and 1935 in Berlin. The hands are those of leading artists, actors, scientists, and writers. Ink and graphite on paper, it measured 84" x 66".

Hill Gallery, Birmingham, Michigan, asked $8500 for this African-American quilt found in Tennessee.

Carl Hammer Gallery, Chicago, Illinois, offered work by Eugene Von Bruenchenhein. These miniature chairs made of chicken bones were $18,000 each and they all sold. Von Bruenchenhein got a big boost by being shown at the Venice Biennale last summer. “We also sold a Von Bruenchenhein painting,” said Hammer.

Amy Finkel of M. Finkel & Daughter, Philadelphia, offered schoolgirl needlework and decorative accessories. The English Windsor chair was $4200 and sold. The sampler top right was stitched in Mary Ralston’s school in Easton, Pennsylvania, circa 1830; the top left sampler was stitched in New Hampshire by Nancy Wason, dated 1827, and was priced at $22,000. The bottom row (from left): the coat of arms was stitched at the Misses Pattens’ school in Hartford, Connecticut, by Elizabeth Lewis in 1800 and was $22,500; the one in the center bottom row was stitched in Philadelphia in 1792 and was more than $100,000; it sold. The bottom right one was stitched on linsey-woolsey by Betty Wells in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1804; it was $18,000, and it sold. The table of long leaf pine was $1100. The two-part wire basket was $575 and sold as did the green glass demijohn.

David Cook Galleries, Denver, Colorado, offered 12 Classic Native American textiles, all made of bayeta (raveled flannel) and indigo dyed wool. On the back right wall was a serape woven of cochineal dyed bayeta, circa 1860, that was $75,000; on the back left, draped as it would have been worn, is a Classic Navajo chief’s blanket with a six-figure price tag; and on the front wall is a third-phase blanket with the diamond contained in the stripes, priced at $65,000. “The New York audience is more educated than in any other city. I had conversations with people who knew what they were looking at,” said Cook.

Clifford Wallach of Manalapan, New Jersey, asked $16,500 for this tramp art marriage bench with pillow included.

Thisraku-fired rabbit by Susan Halls (British, b. 1966), who works in Massachusetts, was $2400 from Cavin-Morris Gallery, New York City.

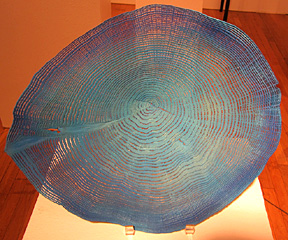

Pascal Oudet is a French artist whose wood-turned sculpture is in a number of museum collections. This sand-blasted oak plate, bleached and colored blue, was $2200 from Cavin-Morris Gallery. |

New York City

The Metro Show opened its five-day run at the Metropolitan Pavilion in New York City on January 22 (it ran through Sunday, January 26), the day after a big snowstorm. It is a new kind of show that old-timers are having a hard time getting used to. There is no printed catalog. The catalog is posted on the Internet with links to each dealer’s Web site. Showgoers can access the catalog from their smartphones or tablets; there’s no need to carry a catalog around the show.

Lots of free tickets were given out for the early opening at 6 p.m., when wine was free for the first hour, but there was a charge for other drinks and for wine after 7 p.m.

The aim of the show is that antiques must be offered as art. For this show it means mainstream and non-mainstream work that includes textiles, wood, folk art, Outsider art, and contemporary art.

Like most shows, this show had its lecture series. New York City dealer Randall Morris arranged dialogues with guest panelist Massimiliano Gioni, who curated The Encyclopedic Palace at the 55th Venice Biennale. The participants in the dialogue, chaired by Morris, were Leslie Umberger, curator of folk and self-taught art at the Smithsonian; Valerie Rousseau, curator of 20th-century and contemporary art at the American Folk Art Museum; Lynne Cooke, chief curator at the Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid; and Cara Zimmerman, executive director of the Foundation of Self-Taught Artists in Philadelphia and collaborator on the Bonovitz collection exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art last year. They questioned the distinctions between Outsider and insider artists. That discussion was followed by a talk on vernacular photography and another on private collections. It focused on the way institutions, curators, private collectors, and dealers search out and choose works of art, especially those that cross genres. Randall Morris is certain that art and design are merging on a global level and that this is the way the art world is proceeding. He hopes that the Metro Show will lead the way. The talks were well attended. Some collectors brought their grown children so there was a contingent of impressionable 20-year olds in the audience.

The promoters came up with the idea that each stand should be “curated,” i.e., have a theme. The result was that some stands had one artist or specialty. It was not so different from the year before. Jeff Bridgman had flags, Amy Finkel brought needlework, Clifford Wallach had tramp art, H. Malcolm Grimmer brought Southern Cheyenne drawings, etc. David Cook brought some dazzling Native American textiles, and Aarne Anton brought edgy folk art, calling it “Carnival of Earthly Desires.” Armstong Fine Art offered a booth of drawings made for a porcelain table service at the French factory of Pillivuyt. The drawings were first shown at the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle. Just Folk exhibited 29 pieces of art by Bill Traylor. Some said that was overkill and that too many Traylors were offered at one time, but the gallery sold four. Moreover, Carl Hammer Gallery and Ricco/Maresca also sold works by Traylor.

Other dealers took a broader approach. Carl Hammer offered a brilliant survey of six Outsider artists whose private worlds he had introduced to the marketplace. Bonnie Grossman of the Ames Gallery also offered work by several Outsider artists she had represented for decades, including A.G. Rizzoli. David Findlay Jr. presented works by artists from the East and West Coasts influenced by Native American “languages” of signs, symbols, and totems. In New York, Steve Wheeler, Robert Barrell, and Peter Busa were known as the Indian Space Group and created a new vocabulary for American abstraction. Findlay’s message was that these works represented the roots of non-objective and Abstract Expressionism on the East Coast.

Allan Stone Projects presented a Wunderkammer featuring the work of ceramic sculptor Dennis Clive and a lot of other objects ranging from a Cornell box to a Tiffany Jack-in-the-Pulpit vase. Samuel Herrup’s Wunderkammerwas a shelf of large and small pieces of American earthenware and English creamware.

What the complainers did not get was that they could go home and explore the exhibitors’ Web sites and see a whole lot more, as well as read about the artists to broaden their horizons. Some complained about the lack of depth. They agreed that tribal art was the show’s strong suit, with William Siegal and Gail Martin showing ethnographic textiles that trumped contemporary works and Douglas Dawson, a new addition to the show, focusing on traditional African ceramics, textiles, and metalwork with a contemporary look. But for collectors of Native American arts there was no Northwest Coast, no Woodland material, no baskets, and no jewelry. They said there has to be a critical mass of dealers in any field to bring crowds down to Chelsea from the Upper East Side in very cold weather.

The same sort of collector said there were not enough dealers in Americana and folk art. (Some of those dealers who used to show at this venue have migrated to the Winter Antiques Show.) The few that are left, such as Tim Hill, brought more contemporary paintings and photography than American folk art. The critics pointed out that not all the art dealers brought works of as high quality as Dolan/Maxwell and Bernard Goldberg, for example.

The show seemed uneven (most shows are) and without a real focus, a smorgasbord, a little of this and a little of that, but that is what it set out to be: an intimate show where you can find something to buy for a hundred dollars to a quarter of a million and where you discover artists who aren’t brand names.

It must have been as hard to get dealers to sign on as it was to increase the audience. (There was one empty booth filled with plastic clouds designed by students at the Pratt Institute.) Many dealers do not do shows anymore; selling at shows is not a sure bet. Carl Hammer, who has done this show since it morphed from a folk art show at the pier into a smaller folk art show at the Metropolitan Pavilion into the Metro Show, thinks the show is going in the right direction, resolving some of the imbalances. “There is no question we want to bring in the best quality we can, and I think this year proved we can be profitable. Each year it gets better.”

Despite all the grousing, some of those who braved the weather said they found the show fun and entertaining. The weather was a downer. Planes and trains were canceled. Nevertheless, 1500 people came, and business was done, some of it dealer-to-dealer; all dealers are collectors.

Carl Hammer sold very well. He sold a set of miniature chicken bone chairs and a painting by Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, a Bill Traylor, and a Joseph Yoakum for a substantial gross. Aarne Anton sold an anniversary tin, a shovel with a curvy snake handle, the pair of fun house mirrors he had at the front of his stand, a rooster shooting-gallery target, an Odd Fellows skeleton, and a “Danger High Voltage” trolley sign. Clifford Wallach said he sold more tramp art at this show than at any other. Roger Ricco of Ricco/Maresca said he sold a Phillip Pearlstein painting to a folk art collector and for the second year he sold a framed selection of brightly colored samples of calligraphy made by a French sign painter.

Stephen Romano is passionate about the self-taught artists he represents and is a consummate salesman. He reported numerous sales of works by Charles A.A. Dellschau, Jana Brike, Dan Berry, and others. He has a following, takes a large stand, and is enthusiastic about this show.

Cavin-Morris Gallery, New York City, curated a broad section of work by the artists it represents and sold works by Melanie Ferguson (ceramics), Guillaume Couffignal (a bronze), Ghyslaine Staelens (a mask), and Melvin Edward Nelson (a watercolor).

Amy Finkel sells American schoolgirl needlework and some decorative accessories and does well too. She has a following who know her Web site and come to see the needlework in person. She likes the idea of selling needlework as art, and she likes the exposure she gets in New York. “I look forward to this show growing,” she said. “I don’t see another top-rate old-fashioned antiques show coming down the pike.” Other dealers said that they have met people here who have become clients.

The 2015 Metro Show will open on Wednesday, January 21, and continue through January 25. For more information, see (www.metroshownyc.com).

Originally published in the April 2014 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2014 Maine Antique Digest