The 2015 Winter Antiques Show

January 23rd, 2015

|

The very rare New York gate-leg table in untouched condition with original butterfly hinges, old finish, and no restoration, red gum, 27¾" high, 52" wide open, 43½" deep, was from Queens County, Long Island. An identical table from the same workshop is pictured in Dean Failey’s Long Island Is My Nation. It is in the Nassau County Museum. Another table is pictured in Wallace Nutting’s Furniture Treasury (fig. 943). It was $85,000, and it was sold by Elliott and Grace Snyder of South Egremont, Massachusetts. The very large folk hooked rug, first quarter 19th century, about 8' square, was marked $95,000. It was found folded up in a closet in a house in Rensselaer, New York, near Albany. The Chinese boy figural hitching post is signed “J.L. Mott Iron Works NY” and is in the 1890 Mott catalog. It was tagged $17,500. The continuous-arm Windsor sold. The rush-seat chairs with pad feet, Hudson Valley, are two from a set of four.

Ralph Harvard designed Kelly Kinzle’s stand. Kinzle sold a Johannes Spitler chest on opening night to a collector on the phone who said he could not get to the show but had seen the picture of it in M.A.D. and wanted to buy it. The price on the tag was $675,000. The Compass Artist box on top was $38,000. The Lancaster schrank was $67,000; the painting of a Seminole Indian, to the left of the schrank, by an unknown artist, sold. A Pennsylvania ladder-back chair is under it. The marine painting is by Antonio Jacobsen. Some of the rarest Philadelphia fire marks known came from a single-owner collection assembled over 50 years. Kinzle said he sold one with an eagle on it to a woman who collects eagles.

The ten chairs hanging on the back wall are by Richard Parkin of Philadelphia, 1830-60. The set was $62,500 from Carswell Rush Berlin, New York City. They are identical to a chair labeled by Parkin at the Landis Valley Museum in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The verd antique, rosewood, and satinwood table by Cook and Parkin is similar to a labeled one made in Philadelphia 1819-33. The faux grain painting is so good that it is hard to detect. It has four drawers and was $65,000. The Philadelphia secretary bookcase (right) is by John Aitken, who made one like it for George Washington, which is at Mount Vernon and is documented by a bill in Washington’s account book. It was $165,000. The plain-style Duncan Phyfe sofa was $19,500. The cellaret is by Duncan Phyfe, 1815-17, with lion monopodia, and was $200,000. The pier table on the back wall is by Duncan Phyfe. It is plate 39 in the Phyfe catalog published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (2011) and was $190,000. The girandole above it, English or American, 1825, was $49,000. The lamps on it are by Messenger & Phipson, Birmingham, England. The wallpaper is French from Carolle Thibaut-Pomerantz, Paris and New York.

This red and black pieced, quilted, and embroidered quilt with elephants, 1910-40, Pennsylvania or Maryland, 90" x 77", was $18,500; the George Washington and Columbia iron stove figures, each 61½" tall, painted white, designed and patented by Alonzo Blanchard (1799-1864), Albany, New York, 1843-50, were $42,000 from Olde Hope Antiques, New Hope, Pennsylvania.

This pair of portraits of a young couple seated on red chairs, attributed to George G. Hartwell (1815-1901) of the Prior-Hamblen school, New England, circa 1840, each 24" x 20", has a Mary Allis provenance; Barbara Pollack wanted $49,500 for the pair. The paint-decorated candlestand, possibly Massachusetts, circa 1800, 28" high, the top 18¾" x 13 3/8", was $29,500. The collection of glass tulips and leaves was $2500. The pair of sculptural Queen Anne side chairs in original red paint, Connecticut, maple and ash, 1790-1800, 46" high x 20" wide x 15½" deep, 18½" sitting height, was $55,000. The seats have been reinforced with flat oval reed to keep the original rush in place.

This small country painted chest with a cutout base on both the front and sides is in a dry pale blue paint. It was purchased in central Maine 25 years ago and was probably made there in the first quarter of the 19th century. It was $11,500. The maple bowl on top of it with very thin sides, late 18th/early 19th century, was $7800. The banister-back side chair with a heart in its crest rail is one of a pair that sold; all were from Peter Eaton. |

New York City

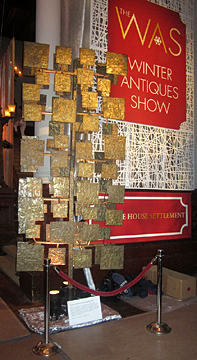

WAS was. The New York Winter Antiques Show, held January 23-February 1, was rebranded THE WAS. The golden phoenix, its logo for 60 years, was consumed into the gold letters “WAS” incorporating the word “THE” and a white snowflake, all on a red ground. The gold initials were on all the banners on Park Avenue, in the entrance to the armory, and on the show catalog. Everyone asked, “WAS the Winter show a thing of the past?” No!

The change in logo was designed to mark a modern incarnation for the 61st edition of the show, a major fund-raiser for the East Side House Settlement in the South Bronx. The message “WAS is NOW” was supposed to prove that antiques are relevant in the modern world and announce a new level of excellence for the show; it is a message hard to sum up in a logo. No one liked it. It was supposed to signal that there was modern design at the show as well as traditional antiques. There was, but modern design was not a big draw. It did not get much advance publicity; all the publicity was late, dealers complained.

There were nine dealers new to the show. British dealers Apter Fredericks, Ronald Phillips, H. Blairman & Sons, and Thomas Coulborn & Sons offered English furniture at a level of quality not seen at this show in years. They sold well and will be back. Daniel Crouch Rare Books, founded by two young dealers in Oxford in 2010 and now in London, brought youth and high-quality maps, globes, and books. Bowman Sculpture, London, and Conner•Rosenkranz, New York City, made sculpture a stronger category, not just part of a stand of American paintings. Kelly Kinzle of New Oxford, Pennsylvania, and Frank Levy of Bernard and S. Dean Levy, New York City, added more Americana to the show. Americana has always been a draw in New York in January.

Although Americana dealers filled just a quarter of the stands, Americana sales were brisk, and the fact that more American furniture sold at the preview than any other category was the talk of the town during the first weekend. Because M.A.D. is the “The Marketplace for Americana,” this review will cover mostly Americana with only a brief mention of American paintings—and there were some very good ones; it is not a survey of the entire show.

The American furniture that sold was sculptural—classic examples that seemed to appeal to a modern aesthetic. Some pieces had old surfaces, and some were refinished; form mattered most. Some sold at prices that seemed reasonable, down from a decade ago, and some were offered at new high levels and sold. “It seems that American furniture has bounced back,” said dealer David Schorsch of Woodbury, Connecticut. “When in recent years has a dealer had to send a truck back to restock his stand as Arthur Liverant did after he sold highboys, lowboys, a chest-on-chest, paintings, and weathervanes?”

Peter Eaton of Newbury, Massachusetts, sold 11 pieces of furniture. Among them was a mahogany serpentine-front chest with a molded-edge top, beaded drawers, canted corners, four dramatic ogee feet, and a molding below the base of a carved shell flanked by C-scrolls. It has an old surface, original brasses, and a label on the back that reads “Made and Sold by W. King/ Salem.” One of only three pieces labeled by King, it was featured in September 1927 in The Magazine Antiques where it was discussed in a three-page article. At that time it was in the collection of pioneer collector Mrs. J. Insley Blair. It sold at the landmark Blair sale at Christie’s in January 2006 for $36,000 to Leigh Keno and then went to a private collection. It appeared on Peter Eaton’s stand priced for less. A collector who was surprised to see an “old friend” he had always admired bought it, saying, “It is of museum quality!”

Other collectors were just as thrilled to buy some earlier American furniture. Eaton sold a butterfly table, circa 1740, with an undisturbed surface, that he said was the best he had owned in over 40 years in business. Grace and Elliott Snyder sold a Long Island gate-leg table, circa 1750, similar to one pictured in Dean Failey’s book Long Island Is My Nation. Nathan Liverant and Son sold a rare flat-top maple high chest made in Preston, Connecticut, circa 1760, featuring fan-carved drawers, freestanding twisted columns, and ball-and-claw feet. Tillou Gallery, Litchfield, Connecticut, sold a sculptural Philadelphia scalloped-top tea table, refinished, circa 1760, reasonably priced at $75,000. Frank Levy of Bernard and S. Dean Levy, New York City, showing for the first time, sold a slant-lid maple desk, a Salem worktable, and a lot more from his shop on 84th Street during the week of the show and after. “I wish I had done shows sooner,” said Levy. “The follow-up from the show has been tremendous; a steady stream of people have come to the gallery and bought.”

Todd Prickett of C.L. Prickett, Yardley, Pennsylvania, sold a small four-drawer Philadelphia chest of drawers with a dark old surface and a Connecticut desk-and-bookcase before the first weekend was over. Windsor furniture sold, too. David Schorsch sold a large Philadelphia comb-back Windsor attributed to Thomas Gilpin; the price was $125,000. Grace and Elliott Snyder of South Egremont, Massachusetts, sold a continuous-arm New England Windsor, and Barbara Pollack of Highland Park, Illinois, sold a Windsor settee made in Maryland and branded by the maker, D. How. Kelly Kinzle sold a Johannes Spitler painted blanket chest with sensational graphics made in the Shenandoah Valley. Kinzle bought it at Freeman’s a year ago in partnership with two other dealers. The asking price was $675,000. It was the most expensive piece of American furniture at the show.

Kinzle also had the most expensive piece of Americana (not counting paintings). He asked $1.2 million for an exceptional tomahawk made of iron, steel, silver, pewter, wood, and porcupine quills that is inscribed “R. Butler” and “Lt. McClellan.” It was made by R. Butler, an armorer in Carlisle and Fort Pitt, Pennsylvania. Richard McClellan carried it en route to Quebec in 1775 but died on the journey. His brother, Daniel, also a rifleman in the company, was captured in the Battle of Quebec. The tomahawk was picked up by the British, taken back to Britain, and entered the collection at Warwick Castle as a war souvenir. It was later in the collection of the legendary American collectors Clare and Eugene Thaw.

There were some extraordinary textiles at the fair, but not many sold. Olde Hope Antiques, New Hope, Pennsylvania, sold a 20th-century quilt with appliquéd and embroidered elephants on a red ground. Stephen and Carol Huber of Old Saybrook, Connecticut, sold a few schoolgirl embroideries.

There were not many sales of naïve portraits. Tillou Gallery, Litchfield, Connecticut, sold a large full-length portrait of a boy by Joseph Whiting Stock (1815-1855) and a pair of portraits by Ammi Phillips (1788-1865) as well as a fine Thomas Chambers (1808-1869) oil painting after a print of the battle between the Constitution and the Guerrière.

There were sales of expensive smalls. A monumental Iroquois burl bowl was sold as a piece of sculpture by Barbara Pollack. A small valuables chest painted green was sold by Grace and Elliott Snyder, who also sold a pair of engraved pipe tongs and a rare pair of circa 1660 English trumpet-form pewter taper sticks. David Schorsch and Eileen Smiles sold a painted paper box that sold at the Sotheby Parke Bernet Garbisch sale at Pokety Farms in 1980 for $7975. It was priced at $35,000 at the show. Schorsch and Smiles also sold a Shaker sconce from the Andrewses’ collection, and a pair of miniature figureheads from the Little and Esmerian collections. The Winter show is where icons of American folk art get recycled.

Two pig weathervanes made by L.W. Cushing and Sons in Waltham, Massachusetts, left the Schorsch and Smiles stand for a new home. Allan Katz of Woodbridge, Connecticut, sold a large early carved and painted wood full-bodied cock weathervane, 1800-25, and he sold most of what was on his stand: a monkey bar diorama, made in a prison, out of of wood, peach pits, fabric, and plastic; the Bingham family Civil War secretary, a tribute to a hero of the battle of Antietam; a German Noah’s ark, from the Erzgebirge region, with eight figures and 173 pairs of animals, birds, and insects; a stoneware bulb pot with incised cobalt decoration; and William “Willie” Howard’s plantation desk made in Madison County, Mississippi. Only two other examples of Willie Howard’s work are known; one is at the Wadsworth Atheneum and the other at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Lori Cohen of Arader Galleries, New York City and Philadelphia, said they had a fabulous show, selling across the board, including maps, botanical prints, watercolors, and a color-plate book. Interest at the show led to sales at the galleries.

Ahead of the Curve, the loan exhibition from the Newark Museum, demonstrated that the museum acquired some of the finest ancient, American, Asian, African, and American Indian art long before those categories of collecting were fashionable. The museum has had its Georgia O’Keeffe white flower painting of the Jimson Weed since 1946. It is similar to the one sold at Sotheby’s on November 20, 2014, for $44,405,000 to Alice Walton for the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. The one at Newark is the first in the series and was acquired from An American Place, the Madison Avenue gallery that Alfred Stieglitz ran from 1929 until his death in 1946.

The Winter Antiques Show continues to be a breeding ground for new collectors and a comfortable place for sophisticated collectors to find good things at a vetted show in a marketplace where it is difficult for dealers to make a profit. The weather is always part of the Winter show. It is January in New York, not Palm Beach. On a snowy day when museums and major highways were closed, people in the neighborhood flocked to the show even though the caterer could not get food to the armory until 4 p.m. “Chubb night” was changed from Tuesday to Wednesday, and 1300 people came since the show stayed open until 8 p.m. The last weekend the show was crowded. The Winter show seems like the last of the old-time vetted antiques and art shows that attract a large buying crowd.

The show is carefully tuned each year by an experienced team led by cochairs Arie L. Kopelman, Lucinda Ballard, and Michael Lynch and its executive director, Catherine Sweeney Singer. They work all year to create a show that produces nearly 25% of the budget that supports the programs at the East Side House Settlement in the South Bronx; 8000 individuals benefit from its programs that include literacy and other educational programs. Of the 300 graduates of the high school programs last year, 75% went to college.

The show is carefully tuned each year by an experienced team led by cochairs Arie L. Kopelman, Lucinda Ballard, and Michael Lynch and its executive director, Catherine Sweeney Singer. They work all year to create a show that produces nearly 25% of the budget that supports the programs at the East Side House Settlement in the South Bronx; 8000 individuals benefit from its programs that include literacy and other educational programs. Of the 300 graduates of the high school programs last year, 75% went to college.

For more information, check the Web site (www.winterantiquesshow.com).

|

|

|

|

Originally published in the April 2015 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2015 Maine Antique Digest

The Bingham family Civil War memorial secretary, Connecticut, dated 1876, walnut, oak, ebony, poplar, pine, maple, metal, glass, muslin, silk, bone, horn, and abalone, 95½" high x 42¼" wide x 19¼" deep, was $375,000 from Allan Katz. It was made by a group of Wells Bingham’s friends in remembrance of his brother, John, who was killed in the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. It was presented to Wells Bingham on July 4, 1876, in Hartford, Connecticut. The clock is a Seth Thomas eight-day brass movement in working condition and is topped with a carved bone eagle with the words “The Union Preserved” on its base. The inlay was tested at the Scrimshaw Forensic Laboratory and was identified as animal bone.

The Bingham family Civil War memorial secretary, Connecticut, dated 1876, walnut, oak, ebony, poplar, pine, maple, metal, glass, muslin, silk, bone, horn, and abalone, 95½" high x 42¼" wide x 19¼" deep, was $375,000 from Allan Katz. It was made by a group of Wells Bingham’s friends in remembrance of his brother, John, who was killed in the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. It was presented to Wells Bingham on July 4, 1876, in Hartford, Connecticut. The clock is a Seth Thomas eight-day brass movement in working condition and is topped with a carved bone eagle with the words “The Union Preserved” on its base. The inlay was tested at the Scrimshaw Forensic Laboratory and was identified as animal bone.  Florence Knoll’s second husband, Harry Hood Bassett, was president of the First National Bank of Miami. She convinced him to commission Harry Bertoia to make ten large sculptures for the bank in 1956. James Elkind of Lost City Arts, New York City, brought two of these large sculptures to the armory to decorate the lobby. They are freestanding and reflected the light, and as the sun changed positions, they never seemed static. They were for sale for $240,000 each. They stood in front of the new logo for Winter Antiques Show to benefit the East Side House Settlement.

Florence Knoll’s second husband, Harry Hood Bassett, was president of the First National Bank of Miami. She convinced him to commission Harry Bertoia to make ten large sculptures for the bank in 1956. James Elkind of Lost City Arts, New York City, brought two of these large sculptures to the armory to decorate the lobby. They are freestanding and reflected the light, and as the sun changed positions, they never seemed static. They were for sale for $240,000 each. They stood in front of the new logo for Winter Antiques Show to benefit the East Side House Settlement.