Michael Weinberg, West Pelham Antiques, Pelham, Massachusetts

October 13th, 2014

|

Michael Weinberg with his miniature basket collection, some of which are for sale. “I do occasionally take one to a show,” he said. They range between $50 and $200.

A tea caddy with inset panels of sampler pieces, one of which is dated 1804. He thinks the caddy may be from Boston. “It was found at a country auction in the center of Massachusetts.” It’s $3450.

A fascinating Albany, New York, sampler depicting the “Federal Bower,” which was a temporary pavilion built in the summer of 1788 to celebrate the state’s ratification of the Constitution. The bower had 11 columns because, at the time, only 11 states had ratified. They are shown on the sampler with the abbreviations of some of the states still visible in reserves above the columns. The piece was executed by Ann Barry, “nine years and ten months” old. She was the daughter of Thomas and Ann Barry. Her father was a well-off Albany merchant and lay leader of the city’s Catholic church. The sampler is $4950.

Three small stuffed animals. The tallest is about 9" tall. The toy dog on wheels to the left is $175. The velveteen rabbit in the middle is $165, and the velveteen dog on the right is $110.

English Prattware finger vase, $685. Weinberg pointed out that the Dutch vases after which this is modeled invariably have at least five fingers, not four.

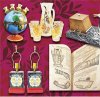

Four potichomania glass balls. Potichomania was all the rage for a little while in the 19th century. You affixed decals to the interiors of glass vessels and then painted or glazed the insides. It was thought that this gave them the appearance of painted porcelain. The largest of these is 8" in diameter. The second largest includes portraits of several early U.S. presidents. They are priced at $695 for the lot.

A tête-à-tête in old black with beautifully shaped arms, $975.

A pair of Mason Decoy Factory glass-eyed mallards, $1195.

Evidence of Weinberg’s “blanket chest disease.” The chest on the bottom is mustard-grained from Pennsylvania, with turned feet, and is $2500. Above it is a green-sponged example, $1000. The small chest on the upper right is from eastern Connecticut with two-tone mustard-painted tombstone panels; it is $2700. To its left is a doughbox in old red-brown wash, $395. The 19" wide chest on top of the doughbox has turned feet and is in grained ocher paint. It is priced at $895.

English puzzle jug in the Wild Rose pattern with a chunk out of the rim, $1650. Puzzle jugs, Weinberg said, “are rare in transferware.” |

In the Trade

Back in the late 1960s Michael Weinberg was studying history in grad school at Columbia University, home to some of the most high-profile student demonstrations of the period. “Relevance,” Weinberg recalled, was the buzzword of the day, and friends asked him what possible relevance could there be to earning an advanced degree in American history.

Weinberg’s answer: “I used to joke and said I was going to open a history store and sell dates.”

Today, he pointed out, that’s sort of what he does. He’s a dealer whose inventory is heavily weighted toward samplers, so, he said, “I sell dates…and, of course, names too.”

About 40% of his inventory is samplers, and another 30% is ceramics with a heavy emphasis on transferware. He edits the Transferware Collectors Club Bulletin.

Both fields—samplers and ceramics, especially historical Staffordshire—“bring out the historian in me,” Weinberg said.

He particularly likes samplers, he said, because “you are dealing with a real person. If you can connect the dots, you can really have a lot of fun.”

In fact, samplers have led to two of his most satisfying experiences as a dealer. In one instance, he recalled, he had acquired a sampler worked by “Wealthy Church.” Weinberg said, “That’s the best sampler name ever. It was out of Hartford [Connecticut]. I found an old posting on a genealogy Web site and called the woman. She practically crawled through the computer to get to me and get the sampler back in the family.”

Another instance occurred at the Brandywine River Museum show in Pennsylvania. He had a sampler worked by “Sarah Brown,” a name so common it was unlikely to ever yield information about its maker. But, Weinberg said, “A woman walked into my booth and said, ‘What do you know about it?” He replied that he didn’t know much of anything.

The woman said, “We know there were three sisters in our family who made identical samplers. We have two. This is the third.” Weinberg marvels at the serendipitous nature of the transaction. The woman, he said, wasn’t even planning to look around the show. She had just come back to pick something up, and because he was located in the vestibule, “She wandered into my space.”

After samplers and ceramics, the remaining 30% of his stock is a country mix: mostly smalls with an admixture of furniture in paint. “I have a disease called ‘blanket chests,’” he said.

Weinberg exhibits at about a dozen shows a year. He doesn’t have an open shop, although he’s happy to meet customers by appointment at his home in Pelham, Massachusetts, a few miles east of Amherst. He’s on a fairly busy road, so he has entertained thoughts of opening a retail space. He said, “I asked the town about retail shops. They said, ‘You need paved parking for twelve cars.’ I said, ‘If I had twelve people in my shop at one time, I’d pay to pave twelve spots.” Since he considers any retail rush to be highly unlikely, he plans to keep things as they are.

The majority of Weinberg’s shows are in New England. He does the VADA show and Cabin Fever in Vermont, Tolland in Connecticut, a couple of Nan Gurley shows, Elm Bank in Wellesley, Massachusetts, and Dealers Choice at Brimfield. Cabin Fever was his first “real” show, and he credits dealer Barbara Johnson with nursing him through it. “She was my mentor; she was great,” he said, adding, “I don’t know anybody better for paint.”

However, he said, his two most profitable shows have been outside New England, at the Chester County and Brandywine shows in Pennsylvania. He thanks Connecticut dealers Joy Ruskin and Lee Hanes for encouraging him to take a gamble on these more expensive venues. He recalled, “At my first Chester County I’m in five figures, something I’d never thought I’d meet.” But he also pointed out that $10,000-plus shows—even in Pennsylvania—have not been the norm.

He said he also sells at the Transferware Collectors Club’s annual meeting, which is held in different places each year, but noted that, these days, only rare pieces are likely to attract buyers. Most transferware collectors already have most of the more common material. “I used to sell like gangbusters,” he said. “Plates and platters don’t really do it anymore. Landing of Lafayette plate? Everyone’s got them.

He likes doing shows, he said, because “I like the interaction with the crowd,” and he particularly likes Pennsylvania because “the crowd is younger and more engaged.”

He said he will probably give up most outdoor shows where he has to worry about the weather. “I’m going to stick to indoor shows. I need help to set up a tent, and Claudia signed up to be with a research guy; she didn’t sign to work as an antiques dealer’s assistant.” (His wife, Claudia van der Heuvel, edits scholarly journal articles. Weinberg said she graduated in the first women’s class at Harvard and is “the smartest person I ever met.” His wife’s mother was press secretary for First Lady Pat Nixon, and her stepfather was a well-known Washington journalist who wrote PT 109.)

Although samplers now make up the largest portion of Weinberg’s sales, he said they are a passion that emerged only fairly recently. “When ceramics started going soft four or five years ago, I developed an interest in samplers.” He tends to deal in mid-level and less expensive samplers. “I’m not at the point where I can handle twenty- or thirty-thousand-dollar samplers.”

Antiques dealer is not Weinberg’s first career. After he left Columbia he moved to Washington, D.C. He noted that at the time—the late 1960s and early 1970s—“New York was an unpleasant city to live in.”

In Washington he worked for Michigan Congressman James Harvey and went on to work as a legislative liaison for the National Science Foundation. “I loved it,” he said. But Claudia didn’t. They decided they wanted to raise their kids in New England. They have two children: Abbie, a librarian at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., and Ken, who does theatrical lighting on Broadway and with shows on tour around the country.

Leaving Washington, Weinberg landed a job as a research administrator at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst where he worked for 20 years before retiring in 2002.

Weinberg traces his interest in antiques—especially ceramics—back to his college days. He went to Trinity College and said, “I spent a summer in college working for the Connecticut Historical Commission.” He was teamed up with a woman named Susan van Rensselaer to conduct a survey of early architecture. “We’d drive around and look at old houses,” he recalled. And they’d also stop at some of Connecticut’s many antiques shops. Weinberg said Van Rensselaer “looked for this strange stuff called mocha.”

Like many young couples of the period, Michael and Claudia furnished with antiques. Even when they still lived in Washington, he said, they would take antiquing trips in New England. A favorite on their route became Jay St. Mark’s shop in Newtown, Connecticut. Weinberg noted with sadness that he and Claudia recently retraced one of their old antiquing routes in Vermont and that now there isn’t a single shop still open.

Weinberg explained that his entry into the world of selling antiques was humble and unplanned. He said, “In 1997 I started on eBay selling some of Ken’s duplicate baseball cards.” But he remembers that period fondly: “When I started on eBay you could go through every item of every interesting category in forty-five minutes.” He recalls his first “score.” “I went to a League of Women Voters book sale and paid five dollars for a stack of [Little] Golden Books at twenty-five cents each.” It turned out that they were exactly the editions that Little Golden Book collectors covet, and they ended up selling for $15 to $25 apiece. It was the sort of occurrence that prompts people to think that being an antiques dealer is easy.

Selling on line also made him realize that people spend money for reasons that aren’t always apparent. He told of one case about a doctor in Idaho. “He bought kids’ books from me, and I noticed he was bidding high on some books I had.” Weinberg contacted the doctor. “I said, ‘These aren’t great books; don’t bid too high on them.’ He said, ‘The closest antiques shop to me is in Salt Lake City, three and a half hours each way. If I have to pay an extra twenty bucks for something I want, it’s worth it.’”

Weinberg has become disillusioned with eBay for any number of reasons, including fee structures and feedback rules. When the site started including postage in determining its final value fee, he said, “That was the last straw.” These days he sells on Ruby Lane. He said, “It’s like early eBay—small enough to get to know people. It’s easy. It’s a passive way of selling. No fuss, no muss, and it’s relatively inexpensive considering the potential payback. I’ll sell nothing for six weeks, and then I’ll sell two or three things. Mostly ceramics.”

Weinberg said that a lot of what he has learned about antiques came to him courtesy of Bill Hubbard, the longtime Pioneer Valley auctioneer. While still working at UMass, Weinberg would attend Hubbard’s weekly Tuesday night auctions. He said, “I asked if I could be a runner. Not for pay, for fun.” Hubbard said “sure,” and after a while asked Weinberg to put some things on eBay for him. He answered “sure,” but added the proviso, “You have to tell me about the things.” That’s how he learned that one can make money in some of the more arcane corners of the trade. He learned, for instance, what a tussy-mussy is and that you can get real money for an early silver one. And he learned that even though there are lots of Erie Canal Staffordshire plates, you can get $1500 for one if it’s a previously unknown scene in an unknown size.

Weinberg carries some country furniture but not lots. He said it makes for a nicer and more varied booth at shows. He doesn’t aspire to dealing in expensive formal pieces. He said, “I can make out a good country table, but I’m not sure I could tell a reproduction highboy from a period one.”

Over the years, Weinberg has taken space at various group shops—among them Antiques at Colony Mill in Keene, New Hampshire, the York Antiques Gallery in Maine, and Antique Associates at West Townsend, Massachusetts—but in recent years he said he hasn’t done well in them. That’s why he switched to shows a dozen years ago; the group shops, along with eBay, were drying up. Today, he said, shows account for 70% of his sales, with Ruby Lane making up the remainder.

Over the years, Weinberg has taken space at various group shops—among them Antiques at Colony Mill in Keene, New Hampshire, the York Antiques Gallery in Maine, and Antique Associates at West Townsend, Massachusetts—but in recent years he said he hasn’t done well in them. That’s why he switched to shows a dozen years ago; the group shops, along with eBay, were drying up. Today, he said, shows account for 70% of his sales, with Ruby Lane making up the remainder.

And even when business isn’t booming, he’s still buying. “I grew up with the philosophy that if a little is good, a lot is better,” he said, adding, “It’s a strange business. It took me four years to convince my accountant, who said, ‘Why are you buying more inventory?’ I said, ‘If I don’t have fresh merchandise, I don’t sell anything.’”

A strange business indeed.

For information, contact Michael A. Weinberg, West Pelham Antiques, 24 Amherst Road, Pelham, MA 01002-9624. On the Web at (www.westpelhamantiques.rubylane.com); e-mail <[email protected]>. Open by appointment or at shows.

Originally published in the November 2014 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2014 Maine Antique Digest