Retha Walden Gambaro, Native American Sculptor

February 28th, 2017

The Potomack Company, Alexandria, Virginia

Photos courtesy The Potomack Company

On February 28 The Potomack Company held an online sale of Native American artwork and artifacts. Of the 236 lots offered for sale, 180 were from the studio and collections of Retha Walden Gambaro and Stephen A. Gambaro. This report focuses on the Gambaro material. All prices include the buyer’s premium.

Retha Walden Gambaro (Creek, 1917-2013) created hundreds of original sculptures in her lifetime. She worked in clay, stone, cast bronze, copper, wood, and any other medium that could be shaped into a work of art. Most of her pieces are in patinated bronze. She took pride in and was noted for her mastery of patina. Her subjects consisted of several general categories. There were traditional Native American figures, such as stickball players, a buffalo dancer, and a figure on horseback. Animals were among her favorite subjects—bears, otters, rabbits, and a dancing turtle were all depicted. But her most powerful pieces were her more abstract images, each evoking its sense of wonder and reflection.

This small bronze sculpture is from the “Attitudes of Prayer” series. This Book of Prayers stands 14" high. The artist’s description for this work is “When we lack words to express our profound feelings, we sometimes reach for a book.” The sculpture depicts an individual sitting cross-legged, hunched over, with an open book in the lap. Dated 1997 and mounted on a black stone base, this sold for $3840 (est. $3000/5000).

This bronze Daughter of Mother Earth stands 12" high and depicts a female with a maize body wrapped in cornhusks with her eyes closed and facing the heavens. Dated 1991 and marked as number 20 of an edition of 48, this bronze brought $2048 (est. $400/600).

Gambaro’s artworks appear infrequently at auction. The Potomack sale represents the first time that her monumental works have come to market, as far as we know, and certainly the first time that a wide range of her sculptures have been offered in a single sale. Presale estimates were very difficult to determine. Following the sale, Elizabeth Wainstein, owner of The Potomack Company, stated that she was encouraged by the results and said that 95% of the lots sold to new collectors of Gambaro’s work. This sale may have set the base for future market pricing.

Special thanks to the Gambaro family and to Elizabeth Wainstein and The Potomack Company staff for allowing me to visit Gambaro’s studio and experience the artwork in situ. Her daughter Anna Gambaro Butler was generous with her time and shared her insights about her mother and her passion.

For additional information, contact The Potomack Company at (703) 684-4550 or see the website (www.potomackcompany.com).

This 51" tall bronze figure, Exultation II, depicts a female with the arms extending to a width of 39". It displays a light, veined stone-color patina. This version and the smaller version carry the same inscription, “Sharing joy and fulfillment with a seasoning of genuine gratitude.” It sold for $6400 (est. $10,000/15,000).

This Native American rabbit stick (also called a throwing stick or throwing club) is from the Gambaro collection. Such sticks are thought to be one of the oldest and most effective food-gathering implements known. This example is from the Southwest and possibly Zuni. It is fashioned from a piece of hardwood approximately 21" long and exhibits red-pigmented decorative bands. This boomerang relative sold for $960 (est. $200/300).

The Story of Retha and Stephen Gambaro

The Potomack Company sale was a reflection of the lives of Retha and Stephen Gambaro. Neither is a household name, and they shared very little in their upbringing, and yet their commitment to their art and dedication to the recognition of Native American art and artists is their lasting contribution our collective heritage.

Retha Walden was a Native American, born in Oklahoma of Creek and British ancestry. Her father was a railroad man, and the family moved several times, ultimately settling in Phoenix, Arizona. Stephen Gambaro (b. 1923) was an Italian American, born and raised in New York City. Family history has it that Stephen lied about his age and entered the U.S. Army at the age of 17.

During the early 1940s, Retha, at that time a single mother, moved to Fresno, California, with her two young daughters. In Fresno she displayed her talent for detail and craftsmanship as a dress designer and seamstress. She must have been good at her craft; she counted among her clients the likes of actress Carole Lombard and future First Lady Pat Nixon.

At the end of World War II, a chance meeting brought Retha and Stephen together. It was apparently love at first sight—they were married 11 days later. The newly formed Gambaro family moved to Richmond, California, so that Stephen could complete his studies at the University of California at Berkeley. Afterward, the family moved several times, landing for a period of time in Mexico City, where Stephen was teaching. During that stint, Retha took it upon herself to teach many disadvantaged women in her neighborhood the skills of using sewing machines as a bridge to improve their lives.

In the late 1960s the family finally settled in Washington, D.C., where Stephen was employed by several federal and city agencies involved with physical rehabilitative services. Retha continued to show her raw talent, working in the design department of a firm tasked with designing in-air refueling apparatus for the government. It was at this time, at age 52, that Retha Walden Gambaro began to explore the world of art that would become her passion for the remainder of her life.

Retha’s successful career as a sculptor had its origin in her failed attempt as a painter. The story is told that with the urging and assistance of a friend, Retha went to an art supply store and purchased paints, brushes, and a canvas. Several days later, the friend called and asked to see the result. Retha advised that she come quickly, as the canvas was outside awaiting the trash truck. Undaunted, the friend took Retha back to the art supply store. This time, instead of paint and canvas, her friend handed her a 25-pound package of sculptor’s clay.

Anna Gambaro Butler, one of Retha’s daughters, reports the result of that purchase. “Mama had a neighbor girl come over and sit so that she could try to sculpt her. She [Retha] said that when her hands touched the clay she felt something take over. She told me, ‘My hands were guided by something outside of me. I couldn’t see what my hands were doing; my eyes were full of tears.’”

Retha had discovered her medium.

Retha Gambaro was not entirely self-taught. She had formal training at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C., and was apprentice to Corcoran master sculptor Berthold Schmutzhart. She also watched and befriended the stone carvers working on the National Cathedral and learned their craft and techniques. Upon his retirement, one of those carvers gave his tools to her.

Retha Gambaro was not entirely self-taught. She had formal training at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C., and was apprentice to Corcoran master sculptor Berthold Schmutzhart. She also watched and befriended the stone carvers working on the National Cathedral and learned their craft and techniques. Upon his retirement, one of those carvers gave his tools to her.

During the early 1970s things continued to take shape for Retha and Stephen. The couple purchased a house in the Capitol Hill area. The home had an old carriage house on the property, which the Gambaros renovated as a sculpture studio for Retha and as an art gallery, which they named Via Gambaro Studio. Via Gambaro Studio became the first gallery in Washington, D.C., to exhibit and promote exclusively Native American artwork and artists.

It is at this point that the history of the Gambaros begins to move in three separate yet compatible directions. Retha became a serious sculptor, working whenever she could in her studio. Via Gambaro Studio became an East Coast focal point for Native American artists and their artwork. And diverse energies seeking to establish a national museum celebrating Native American art and culture began to come together. At or near the center of everything was Retha Walden Gambaro.

As well-known and not-so-well-known Native American artists began to display their talents at Via Gambaro Studio, it acted as something of a lightning rod for those most active in the movement to establish a national Native American museum. In 1980 the Amerindian Circle was founded. That organization is credited with kick-starting efforts that would ultimately see the establishment of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian. As president of the circle, Retha was instrumental in organizing the Kennedy Center’s 1982 fund-raising gala, “Night of the First Americans,” under the patronage of President and Mrs. Ronald Reagan.

This colored etching on embossed paper was part of the Gambaros’ collection. The artist was Helen Hardin (Santa Clara Pueblo, 1943-1984). This example of Hardin’s work appears to be a geometric and stylized version of a Mother Corn or Mother Earth figure. The etching measures 19½" x 16½" and is signed in pencil lower right Tsa-Sah-Wee-Eh along with a pictograph for Little Standing Spruce, Hardin’s Native American name. The etching is number 30 of an edition of 50. It sold for $1152 (est. $350/500).

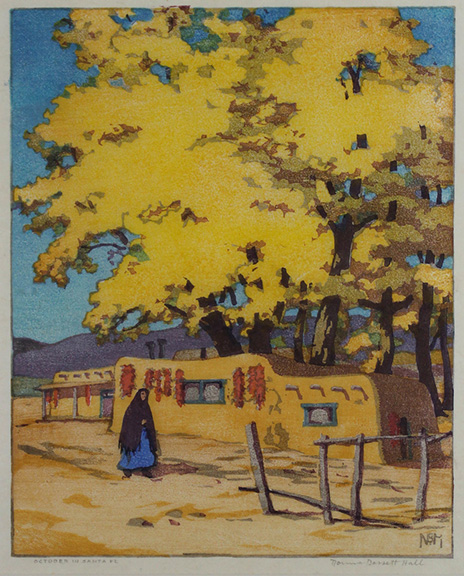

This colorful woodblock print is by Norma Bassett Hall (1889-1957). October in Santa Fe is signed by the artist in pencil, lower right. The block also has the initials “NBH.” Norma Bassett Hall was an Oregon native who moved with her husband, also a printmaker, to Kansas, where she was the only woman founding member of the Prairie Print Makers. Later, they relocated to Santa Fe, and she is listed among noted Taos and Santa Fe art colony painters. This 10½" x 8½ print (not from the Gambaro consignment) sold for $1408 (est. $800/1200).

At about this same time period, Stephen took a road trip west. As an accomplished photographer, it had been his practice to take large-format portrait photographs of Native American artists who exhibited at the Via Gambaro Studio gallery. The Gambaros had supported the artists in their gallery and developed an extensive collection of their works. On this trip he visited with other artists and leading Native American figures, recorded their images, and added to the family collection of original artwork.

When Stephen retired from his rehabilitation-related career, he and Retha moved to a home in Stafford County, Virginia. A natural-light studio was constructed on the property, and it was there that Retha created what are arguably her most important works. In 1995 Retha was commissioned by a private collector to create a series of sculptures. Retha titled the 36-piece series “Attitudes of Prayer.” Each sculpture is carved from stone and depicts a prayerful attitude or stance. Although many of the pieces are abstract, each evokes a sense of spiritual power. Each of the sculptures is accompanied by a thought-provoking quotation from Retha.

Before the “Attitudes of Prayer” sculptures were delivered, molds were made of each one. Those molds were cast in bronze, and patinas were carefully selected for the surfaces. From 2011 to 2014, a major retrospective of Retha’s work was exhibited at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, her childhood home.

These hands hold a dove. The artist’s inscription reads “Sought by so many, destroyed by so few!” The title is simply Peace. The 33" high bronze, dated 1997, has patination imitating finely carved and polished stone. This example from the “Attitudes of Prayer” series sold for $3200 (est. $5000/8000).

One of the “Attitudes of Prayer” series, Family, was particularly well received. As her final artistic project (and at the urging of collectors) Retha began work on a reduced-scale version of Family. Anna Gambaro Butler stated that until Retha was unable to come to the studio, she and her mother would work together on the sculpture, smoothing and refining the surface. Sadly, the small version of Family has never been cast.

According to Dr. Letitia Chambers of the Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona, this sculpture, Family, became something of an interactive piece during the 2012 Attitudes of Prayer exhibit at the museum. The 34" x 46" sculpture depicts two adults and two children seated in an embrace. The bronze was installed on a low base while at the Heard Museum, and children would gravitate to the family, occasionally joining the group hug. This family did not sell during the online sale but did find a new home in post-sale activity and brought $9375 (est. $15,000/20,000).

Originally published in the May 2017 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2017 Maine Antique Digest