Christie’s, New York City

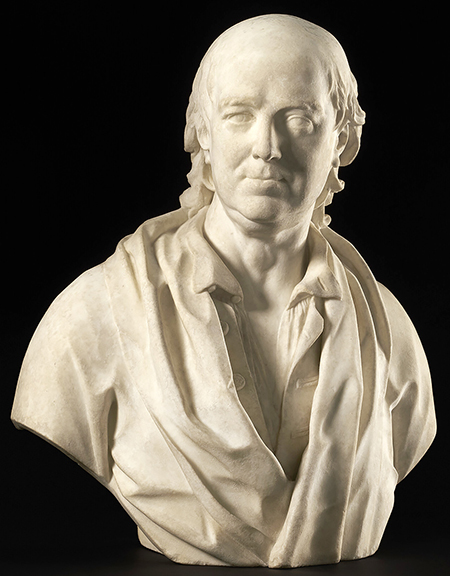

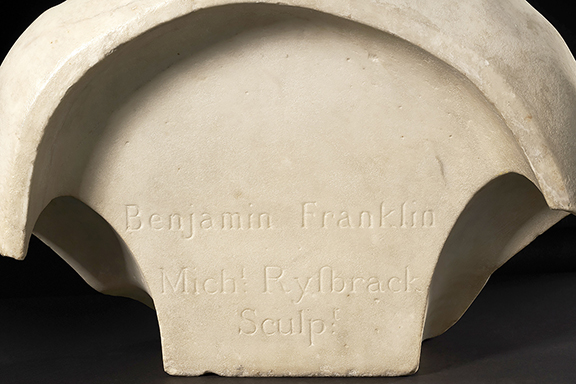

A white Carrara marble bust of Benjamin Franklin by John Michael Rysbrack (Flemish, 1694-1770), 1757-62, inscribed on the reverse “Benjamin Franklin / Michl: Rysbrack / Sculpt:” sold with an associated later marble column for $441,000 (including buyer’s premium) to an online bidder in Connecticut at Christie’s sale of classic and decorative art on February 7 in New York City. The buyer remains anonymous.

Photo courtesy Christie’s.

Photo courtesy Christie’s.

There were 24 lots in the sale, and just 13 of them—a 54% sell-through rate—sold for a total of $2,528,820. Only one lot brought more than the Franklin bust. An Imperial jeweled and enamel gold-mounted hardstone study of a bearberry branch in a crystal vase, made by Fabergé workmaster Henrik Wigström (Finnish, 1862-1923) in St. Petersburg, 1910-11, sold for $529,200 (est. $200,000/300,000). Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna (1853-1920), daughter of Emperor Alexander II of Russia, had purchased it from the St. Petersburg branch of Fabergé on April 30, 1913, for 250 rubles.

If the 23¼" high marble bust of Franklin had been offered in an Americana sale, might it have brought more? It was instead offered in a small sale of mostly European decorative art with the exception of a large Tyrannosaurus rex tooth from South Dakota that sold for $214,200 (est. $100,000/150,000). A pair of George II mahogany and parcel-gilt chairs attributed to Benjamin Goodison, possibly after a design by William Kent, 1754-56, brought $189,000 (est. $50,000/80,000). An English William and Mary japanned secretaire-cabinet with a $100,000/200,000 estimate failed to sell, and an unreserved suite of Louis XVI gilt walnut seating furniture—two canapés, two marquises, and two fauteuils—with Beauvais tapestry upholstery sold unreserved for $17,640 (est. $60,000/100,000).

Leslie Keno with John Michael Rysbrack’s sculpture of Benjamin Franklin. Pennington photo.

The Franklin bust first made news when it was discovered in 1986. Since its last appearance at auction in 2014, new information uncovered in papers in the collections of the American Philosophical Society documents that it was in Benjamin West’s studio when he was painting his unfinished but hugely important painting American Commissioners of the Preliminary Peace Negotiations with Great Britain, also known as Treaty of Paris, begun in 1783, now at the Winterthur Museum, Garden, & Library in Delaware. The bust remained in West’s studio until 1784; because Franklin was not able to make the trip from Paris to London to sit for West, the bust served as a model while West was working on the painting.

Christie’s catalog pointed out that this bust of a “young and virile Benjamin Franklin, by one of Europe’s most celebrated sculptors, is the earliest and most naturalistic and vibrantly alive rendering known of Franklin.” It was carved from life during Franklin’s second visit to London between 1757 and 1762, as by the time of Franklin’s third visit in 1764, Rysbrack was long retired, had sold most of the contents of his studio, and was in poor health. Franklin’s relaxed appearance, dressed in indoor clothing, with an open shirt and without a wig, was a style that became fashionable throughout the latter half of the 18th century. It conveyed the sitter’s status as a cultivated intellect and man of letters.

The Rysbrack bust predates by nearly 20 years Jean-Antoine Houdon’s 1779 marble bust of then-73-year-old Franklin that the artist brought to America in 1785, when he was commissioned to create a life mask of George Washington at the request of Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. Houdon later used the mask as a model for his full-length statue of Washington for the Virginia State Capitol. The Philadelphia Museum of Art paid $2,917,500 (est. $3/4 million) for Houdon’s marble bust of Franklin at Sotheby’s in 1996.*

Rysbrack’s work also predates the Franklin bust by Philadelphia carver Martin Jugiez (c. 1730-1815) that dates from the late 1770s to circa 1800. That bust sold for $175,000 to the Chipstone Foundation at Sotheby’s in January 2016.

The Rysbrack bust of Franklin comes with a good story, first told in 1986 after it was discovered in the U.K. and came up for sale at Christie’s in London. When Patrick Crawley was a boy, he took daily walks with an elderly neighbor and the man’s black spaniel, Monty. When the dog owner moved away in the early 1950s, he gave the eight-year-old Crawley the marble bust that the old man called “Benjamin,” on whose head he deposited his hat at the end of their daily walks.

By 1986 Crawley was the owner of a pub called the Carpenters Arms in Felixkirk, North Yorkshire. After he read in newspapers that 18th-century marble busts were selling for six-figure sums, he brought the bust inside from his balcony and called Christie’s. A Christie’s expert told him that it was signed on the back by Rysbrack, identified the subject as Franklin, and said it was at the time an unrecorded work by the prominent 18th-century Dutch-born British artist and sculptor John Michael Rysbrack, and the earliest known bust of Benjamin Franklin.

Crawley consigned the bust to Christie’s, which sent him to New York City and Philadelphia to promote the sale. Nevertheless, when the bust was offered in a sale of European works of art sale at Christie’s in London on April 24, 1986, it did not reach its reserve. After the auction, Christie’s sold the bust to a private collector living in England whose name remains anonymous.

The bust remained in obscurity until 2014 when the collector who had purchased it privately contacted Sotheby’s European paintings and sculpture department in London and asked Sotheby’s to offer it at auction.

Before the bust was auctioned in London, it was exhibited again in New York City. At Sotheby’s in London on July 10, 2014, it sold for £483,000 (approximately $825,000 at that time) to a newly retired oil executive from Texas on the advice of his brother-in-law Leslie Keno.

Keno thought the bust was a great investment at the time. Over the years, Keno has been trying to sell it for his brother-in-law without success. Recently they decided to consign it to Christie’s in New York City for auction. It was on view in Christie’s lobby during the preview of the Americana and American paintings sales in late January and again during the week before the February 7 sale. A long essay in the online catalog incorporated all of Keno’s research and explained that the bust had been cleaned and conserved, and it presented the new documentation that was uncovered since the bust last sold in London that associates it with Benjamin West.

The catalog notes that it “was fitting that Rysbrack was commissioned for Franklin’s portrait bust” because “Rysbrack was one of the most accomplished and celebrated sculptors working in England in the first half of the 18th century.” The impressive list of his commissions and sitters includes royalty, aristocrats, powerful politicians, and brilliant Enlightenment figures, among them Sir Isaac Newton. The Newton bust by Rysbrack may possibly be the one that appears in one of the earliest paintings of Franklin, painted by David Martin in 1767 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. The bust of Newton in the painting may also be by Louis-François Roubiliac.

The $441,000 paid in the February 7 Christie’s sale for the earliest marble portrait of the American who signed all four documents that created the United States—the Declaration of Independence, the Treaties of Alliance, the Treaty of Paris, and the Constitution—seems like a good buy just a year before the country celebrates its 250th birthday.

For more information, see the website (www.christies.com).

*Jean-Antoine Houdon’s bust of Franklin, carved in 1779, was brought to this country in 1785 when Houdon was commissioned to carve the standing statue of Washington for the Virginia State Capitol. It once belonged to Governor DeWitt Clinton of New York as well as Mayor Abram S. Hewitt of New York City. When it came into the hands of New York dealer James Graham in 1939, he sold it to collector Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge for $5500. She displayed it in the lobby of her rarely used Fifth Avenue mansion until a guest bumped into it at a party. She then had it crated and moved to the basement.

When the bust came up for sale at Sotheby Parke Bernet in 1975, Graham was bidding on behalf of a Philadelphia collector who wanted to make it a bicentennial gift to the White House, but he let it go to the British Rail Pension Fund for $310,000, then an auction record for any Houdon sculpture. The British Rail Pension Fund cashed in on its investment in 1996 when the bust sold for $2,917,500, an auction record for any work by Houdon, to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Originally published in the May 2025 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2025 Maine Antique Digest