It’s a little like admitting to being a heretic, but while working for 17 years as a reporter for M.A.D., my favorite items to write about weren’t pieces of furniture. They were pieces of paper. I loved to write about things like rare books and ephemera. Chests of drawers, not so much. It didn’t have to be expensive paper, although I did write about the letter that DNA’s co-discoverer, Francis Crick, wrote to his then 12-year-old son, Michael, that sold at Christie’s in 2013 for $6.05 million (including buyer’s premium). I also wrote about a handwritten vellum copy of the 13th Amendment, one of only 14 such Lincoln-signed copies known. The document that abolished slavery in the United States sold at Sotheby’s in 2016 to well-known philanthropist David Rubenstein for $2,410,000. I covered the sale of a so-called Columbus Letter, too.

That sold at Bonhams in 2017 to William S. Reese of the eponymous rare-book firm in New Haven, Connecticut, for $751,500. For a Swann Galleries auction report in 2016, I noted that Reese also bought a rare seventh edition of the Bay Psalm Book with Salem witch trial provenance for $221,000.

The author’s fake-book ceramic canisters.

I came to M.A.D. in 2003 already preferring words rather than wood. I was a writer, not a collector, although my husband of 51 years was a dealer and still is an ardent collector of timepieces, and I have bought paper items myself from time to time. For a while, in the 1990s, I did try to collect something: fake books. They did intrigue me. But I didn’t get much beyond a set of 20th-century ceramic canisters from King Arthur Flour. I respect and admire collectors, but I just don’t have the proverbial collector “gene.”

Besides writing professionally since 1973, I have been a diary-keeper since age eight, starting with the blank diary my parents gave me for a birthday gift that year, 1959. They knew I already liked writing, but I doubt they imagined I would write anything more than brief descriptions of events in the little book that locked with a key. Neither of them had been diary-keepers. Their conception of a diary probably was like that of the New Hampshire boy whose 1925 volume I once owned (and have since sold) that sums up January 10 in just two lines: “Earthquake last night. Pancakes for breakfast.”

So my introspective tendencies came from somewhere else. Maybe it was a secular version of the meditation I learned at my Catholic grammar school. Also, our household was not particularly the child-centered kind that encourages kids to talk just for the sake of it. I may have had more to say than anybody wanted to hear—and apparently also had more to write than anyone wanted to read. To paraphrase Emily Dickinson, not only did the world never write to me, but my very own pen pals didn’t write back as quickly as I wished they would. In Isabel Colegate’s The Shooting Party, a grandfather says to his granddaughter: “It’s not a bad idea to get in the habit of writing down one’s thoughts. It saves one having to bother anyone else with them.” Even before I read that 1980 novel, I understood that piece of advice, which really suits me much better than the Oscar Wilde line about bringing your diary along when you travel, so you’ll have something sensational to read on the train.

Pages from the John Albee diary. Courtesy Swann Galleries.

This is by way of saying that I always had a soft spot for diaries and journals that I came across on my antiques beat. As for the difference between the two, diaries are day-to-day personal records, while journals are more or less themed, like a garden journal or travel journal. But the genres, so to speak, do often cross and meld. Swann Galleries always has a good selection of both diaries and journals at its Americana sales. At that same Swann sale where the Bay Psalm Book was sold to Bill Reese, the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston paid $9375 for the 19th-century manuscript diary of John Albee (1833-1915), who went to Phillips Academy, the four-year prep school in Andover, Massachusetts, where I live. Its 241 pages cover May 16, 1853, through January 24, 1861, while Albee was a student first at Phillips, then at Harvard Divinity School. It continues through his first years as a Unitarian minister. The young Albee reveals his spiritual doubts, writes a painful narrative of an unrequited love, and probes his inner life in a surprisingly modern way. “There is something of the feminine in my character,” he reflects on July 3, 1855. “There is more than anyone knows in my body. I am too sensitive and confiding for a man.” He was also a Transcendentalist poet and writer, and a friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and the Alcott family—reasons enough why the price went beyond the diary’s modest $4000/6000 estimate.

At the time of the sale, Rick Stattler, director of Swann’s books and manuscripts department, said of its institutional buyer: “That’s a perfect home for it. It’s a Massachusetts story, and although Albee didn’t kill any whales or ride across the Rocky Mountains, his diary certainly has more literary and philosophical interest than most of the diaries we handle.” Or most of the diaries and journals out there, period. That goes for the diaries and journals of notable people. Still, there are always elements of value. I remember reading portions of the diaries of Historic New England’s founder William Sumner Appleton some years ago for one project or another. They were as boring as cement. Still, they not only served as a timeline of his life; they also provided evidence of his rather lugubrious personality, despite the great things he accomplished for historic preservation.

Coverage of the New York International Antiquarian Book Fair in March 2020 and a couple of Swann sales shortly after that were the last M.A.D. assignments I agreed to take on. Once COVID struck, I decided it was best for me to return to independent writing projects I could accomplish at home. Given travel restrictions, even to nearby Boston, it especially made sense for me to write about what was nearest at hand: my town. Fairly soon my focus became the Andover Theological Seminary (ATS), a three-year divinity school whose life span on the Phillips campus was a nicely circumscribed single century, 1808 to 1908, after which it attached itself to Harvard before merging with the Newton Theological Institution in Newton, Massachusetts. (The Andover-Newton Theological School has since merged with Yale Divinity School.) I had already published Huddle Fever, a book about Andover’s next door neighbor: the old textile mill city of Lawrence. At its most basic, Huddle Fever is a history of what Lawrence once produced: cloth. The Missionary Factory, as I came to call my new project, is a history of what Andover once produced: men of the cloth. Why it was founded in Andover; how it developed into an international ecclesiastical powerhouse that initiated the American Protestant mass missionary movement; how its graduates and their supporters fit into the broader cultural, economic, and political context beyond their theological concerns and conflicts; and what precipitated ATS’s downfall, which was actually a long, slow, inevitable slide rather than a quick, preventable toppling—that is the story The Missionary Factory tells.

During the early days of the pandemic, I could do plenty of research online and in books I had close at hand. After the worst dangers were over and vaccines were helping us to protect ourselves, I was able to go to archives, where I have been going ever since. That’s where I was on March 13 of this year when I experienced a nice surprise. I was at the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS) when I once again came across the Albee diary. It was among the items I had requisitioned for that day, since even though Albee attended Phillips, not ATS, I am always very interested in what else was happening on that campus in the 100-year period of ATS’s existence. And the prep-school students and seminarians did intermingle with each other.

Except that I had completely forgotten about having reported on the Albee sale, or that I had ever even seen the thing! When it came up in the MHS catalog when I searched “Andover,” I did not remember the Albee name. I knew only that it was something I thought I might want to read. It wasn’t until it was on the desk in front of me that it suddenly dawned on me. I looked up its provenance just to be sure. Yup, the very one, now in a public collection for me to use.

As I regularly do at archives, in order to be efficient I take images of the pages I want to read and then I do so at home, where I can magnify them on my computer screen. When material is handwritten, as Albee’s diary is, it is an almost imperative step in order to decipher words that would otherwise be illegible. So along with the rest of my harvest that day, I took images of the 60 pages that cover Albee’s Phillips years, and I startled the desk librarian as I was leaving by saying “Thank you for buying this,” since of course she had nothing to do with it.

A notation on a blank page in the front of the Albee diary says it was “found in the library of Mrs. John Albee at the Albee summer house in Chocorua, New Hampshire after her death. It was purchased from the house in August 1940.” It was signed Norman D. Fletcher (1898-1985), who was himself a Unitarian minister. Given that, I realized I should be looking heavenward and thanking him, along with the Albee widow, who left it there to be bought. And bought again, I guess, when it left Fletcher’s hands or estate and went on to Swann.

One month after MHS bought the diary, Susan Martin, senior processing archivist for the institution, wrote about the then new acquisition, but I didn’t discover her online essay until I started writing this. It provides information about Mrs. John Albee. There were actually two of them. The first was Harriet Ryan (1829-1873), whom John Albee married in 1864; the second was Helen Rickey (also spelled Ricky, 1864-1939), whom he married in 1894. There were four children, all of whom he had with the first Mrs. Albee, and all predeceased their father, so none of them was the keeper of this volume. Apparently it was the doing of Helen Albee, who, according to the Portsmouth Athenaeum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, was an early founder of the New Hampshire arts and crafts movement who established a cottage rug-hooking business that employed local farm women.

John Albee lived for many years in New Castle, New Hampshire. At some point he moved to Chocorua, an unincorporated community within the town of Tamworth, New Hampshire. So even having moved to a different house, when so many things get tossed, he first saved the diary, and then Helen Albee did, for the next 24 years. That brings me to my message and why I am writing this when I really should be poring over the pages of John Albee’s inked script. If in doubt, don’t throw it out. For The Missionary Factory project I have read scores of missionaries’ memoirs, based on diaries, journals, and correspondence. Most of the published versions were invariably prettied up by their editors for a variety of reasons, including monetary ones. The missions thrived on donors to the cause. But if what would-be donors read was too grim, the cause might seem hopeless, so why bother giving to it? On the other hand, if it was too cheerful, the missionaries might not seem to need their financial help after all, so again, why bother, especially if there were other causes nearer at hand? Editors and their publishers, often affiliated with missionary societies, felt it their Christian duty to take liberties for the sake of the souls of the “heathen.”

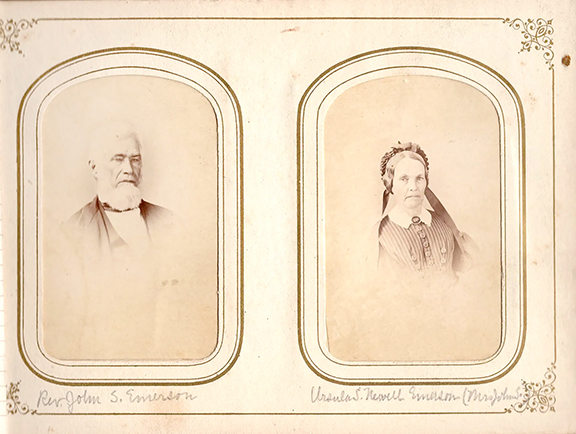

Cartes de visite of John S. Emerson and Ursula Sophia Newell Emerson. Courtesy James E. Arsenault & Company.

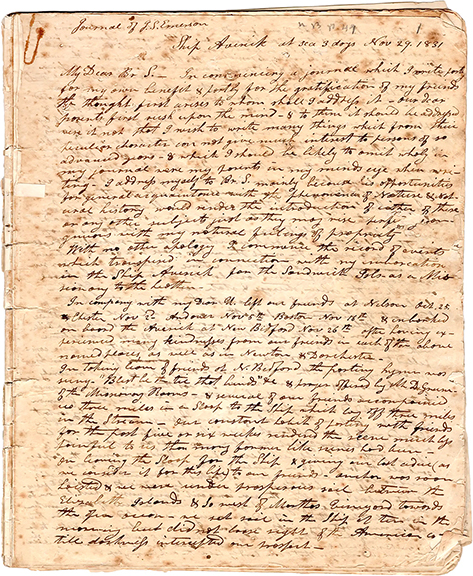

Page from the journal of John S. Emerson. Courtesy James E. Arsenault & Company.

James E. Arsenault & Company, Arrowsic, Maine, is a dealer in printed and manuscript Americana, African Americana, Western Americana, ephemera, maps and views, historical prints, literature, fine press, photography, and autographs, as well as fine and rare books in a variety of fields. I have been aware of a fabulous missionary archive for sale on his website for a long while. It was saved by the family of John S. Emerson (1800-1867) and his wife, Ursula Sophia Newell Emerson (1806-1888), who arrived in Hawaii as missionaries in 1832. The Reverend Emerson was a member of ATS’s class of 1830, so he was of particular interest to me, especially since both he and his wife wrote so candidly about their lives, including their struggles. One of the Emersons’ seven sons, Oliver Pomeroy Emerson, edited some portions of their journals and published them in 1928 as Pioneer Days in Hawaii, but of much more value are the unedited originals. On September 24, 1832, for example, Ursula wrote about their housing conditions and how she and John were coping with them: “Mr. E. [as she referred to her husband] has made me two cupboards which I value much. Everything that is not secured in some way is constantly liable to be destroyed by the herds of vermin with which we are annoyed. The mice & cockroaches leave nothing untouched which is within their reach. [Unless] we use the greatest caution the cockroaches will get into our trunks & drawers & devour our clothing. Some of the missionaries have been obliged to sleep in gloves to keep the animals from gnawing their fingers...& you might as well think of flying away as of ridding yourself of fleas.”

The son’s edited version of the paragraph leaves out his mother’s vivid details, giving us only this tepid version: “I cannot tell you how we are troubled with insects. Mosquitoes, fleas, little red ants, cockroaches and mice overrun us and we must protect everything. My husband has made two cupboards which are very valuable.” Meh.

In an email of March 17, Jim Arsenault told me that the Emerson archive, which he owned in a partnership with three other parties, was sold earlier this year. The deal was done by one of the other parties, who “has not revealed the identity of the buyer,” Arsenault said. “All I know is that it was purchased by a private customer who is donating it to an institution.” That’s good news for researchers like myself. We rely on materials like these that private collectors very often do donate to libraries, archives, and other public research centers.

There is a word in preservation circles that has lately come to the fore. It is pastkeepers. Its popularity, if not its coinage, started with a book by history professor Michael C. Batinski titled Pastkeepers in a Small Place: Five Centuries in Deerfield, Massachusetts, published in 2004. It may be that Mrs. Albee was a conscious pastkeeper. Just as likely, she was simply one of those old-time Yankees who never threw anything away. In September of 2010, a triple ballroom inside a cavernous convention center in Worcester, Massachusetts, became the setting for the four-day, nearly 2400-lot Green family auction that I wrote about for M.A.D. Orchestrated by auctioneer Richard W. Oliver of Kennebunk, Maine, the sale featured the belongings of ten generations of Greens dating from the 17th century through the 20th. Besides the usual estate silver, china, glass, paintings, textiles, jewelry, furniture, dolls, toys, and games, there were journals, diaries, ledgers, household expense books, wills, broadsides, posters, photographs, newspaper clippings, postcards, invitations, diplomas, maps, hair samples, railroad and ferry passes, stamp collections, coins and paper money, and on and on and on. Oliver said when he and his team started going through it all, he found 10,000 pieces of correspondence alone.

“Like many other families imbued with the Puritan tradition, the Apleys have not been in the habit of destroying letters or papers,” the omniscient narrator remarks of a Boston Brahmin clan in John P. Marquand’s 1937 epistolary novel The Late George Apley. In a letter to his sister, Amelia, George Apley writes: “In fact, Hillcrest and Beacon Street are so full of family silver, furniture, papers and draperies that there is not room for anything which is not family.” The Green family was very much like that, and private collectors of all stripes and people bidding on behalf of public collections flocked to the event. Some came because they were interested in Andrew Haswell Green (1820-1903). An influential New York City official, preservationist, and reformer, he played crucial roles in the creation of Central Park, the restoration of fiscal control to City Hall after the Boss Tweed years, and the consolidation of New York City into today’s five boroughs. Another draw to the auction was Andrew’s younger brother Samuel Fisk Green (1822-1884). As a seven-year-old, Samuel noted in his diary one day that he had knitted himself a pair of mittens before breakfast because his hands had been cold. As an adult, he became a physician who made a mission of bringing modern medicine to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). He also provided for the people spiritually by, for example, translating the Bible into Tamil. Mankind may owe debts to those two Greens, but a series of unsung family members, ending with Julia Thompson Green of Kennebunk, who died on July 5, 2009, at age 73, were the ones to whom all the stuff at the auction had trickled down.

As people downsize and more and more houses get cleaned out by relatives or friends without a sense of history, the dangers are clear. “I don’t ‘get’ paper,” a clock collector once said to me when I told him I was going to an ephemera show over the weekend during my reporting days. I thought of his comment when Lisa Holley, Jim Arsenault’s wife, said to me, unprompted, early on the second day of the New York book fair in 2013: “In the big sea of people who don’t get it, it’s nice to be in a place where people do.”

Story. History. Each word has the same root. Some collectors aren’t great storytellers; they don’t say much. Others you can’t shut up. Either way, I submit that collectors are our most crucially necessary chroniclers of history—through objects, wood and otherwise; through material culture, as it’s called in academe; through things, including things made of paper. But the same goes for the pastkeepers, savers, and people who just can’t bring themselves to throw something away.* “You get one person who doesn’t understand, and he can wipe out history,” Robert Opie once said—he, who started collecting commercial packaging, like cereal boxes, in his native Great Britain in 1963, at the age of 16, and founded the Museum of Brands, Packaging and Advertising in London’s Notting Hill in 1984. There is what he shudderingly terms “the 30-second gap between ‘out it goes’ and ‘I wonder if anyone might be interested in that.’”

For more information about the author, her publications, and her current project, see (www.jeanneschinto.com) and (www.themissionaryfactory.com).

*Hoarders are different. See my “Hoarder or Collector? Some Readings and Reflections,” M.A.D., November 2017, pp. 10-11-B.

Originally published in the May 2025 issue of Maine Antique Digest. © 2025 Maine Antique Digest